SILA: the breath of the world

08 March 2016 by Marc Taddei

I have had a particularly exciting start to the year, waking up on the Milford Track on New Year’s day, after running the entire track the day before. Following this, my wife and I enjoyed a bit of the beautiful summer weather, driving back up the South Island of New Zealand.

As an example of the sublime in nature, here is a view from Lake Ohau – one of my favourite parts of the country…

We stopped off in Wellington on our way back home, spending the evening with wine-loving friends, consuming some of the greatest wines made in France – Chateau Mouton Rothschild 1982, Chateau Leoville Las Cases 1986 and the elusive Jean Louis Chave Hermitage “Cuvee Cathelin” 2000, among them! It was an extraordinary night of sublime wine!

Speaking of sublimity, last weekend, I had the great good fortune to direct and perform in John Luther Adams’s extraordinary “Sila: the breath of the world” for the New Zealand International Festival of the Arts! These two performances were the New Zealand premiere of this work.

Sila is a work designed to be performed outdoors, utilising up to five different choirs of 16 musicians each. During the performance of the work, the listeners become aware of more than just the entrancing music, rather they (almost unwittingly) also absorb and pay close attention to the ambient sounds that are already present in the environment that surrounds them – be they the sounds of nature or the sounds of a bustling city.

Here is the composer speaking with Radio New Zealand, in advance of our performances.

The work is precisely written out, based on the fundamental pitch of B flat and the subsequent overtones that occur (in nature) above this pitch. The overtone series has had a profound effect on how music developed throughout history, but as music continued its progression, composers and theoreticians needed to adjust or temper the actual pitches in order for music to remain harmonious and especially so that composers could easily modulate between keys, while avoiding “wolf intervals”.

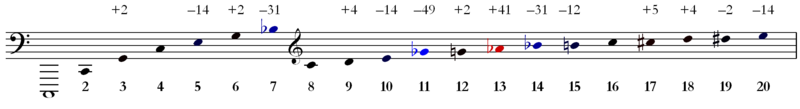

In nature, the resultant overtones above the fundamental are first the octave (which is exactly twice as fast in terms of frequency), and from that point, the overtones start to sound slightly different in terms of frequency than we have been trained to hear in tempered tuning. Thus, the fifth (2nd overtone) is slightly higher (by 2 cents) and the third (4th overtone) is notably flat (by 14 cents). Now listening to these first 5 notes (including the fundamental) results in a major chord – one that is actually beautifully in tune (if not so easy to modulate from due to its lack of temperament) and tuning a major chord this way is a sure fire way for the end of a Berlioz overture to sound even more vibrant. Once the seventh (6th overtone), things start to unwind to our tempered ears. This note is 31 cents flat and as such feels far too low to our tempered sense of hearing…

One can easily hear these overtones and the variance with tempered tuning. If you go to a piano and play a low note, eventually you will hear higher overtones whistling above the fundamental. At this point, play the harmonic that is sounding on the piano (not the octaves of the fundamental) and you will hear that the piano is not in tune with the harmonic. Please see below for the adjustments that need to be made for the overtone series, starting from a fundamental of C…

While there have been a number of works that take advantage of the implications of true harmonic resonance – notably the horn writing in Britten’s superb Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, John Luther Adams constructs his entire work on these implications, moving from the lowest fundamental to the very top of the instruments’ tessituras. The composer treats these naturally occurring notes and intervals in an elaborately worked out progression that becomes extraordinarily absorbing during its performance, as the resultant overtones begin to take over and replace the starting fundamental as the focus of the listener’s attention. For instance, at one stage (around 45 minutes into the performance) I played the fundamental B flat and it came across as the dominant seventh of a C chord.

In our performances, we positioned the musicians around the city square of Wellington – with a number of the trumpet players on the roof of one of the buildings.

As you can see, the public was free to walk around, or sit amongst the musicians. In the middle of the square, we positioned the choir of 16 vocalists, each using megaphones to naturally amplify their voices. We instructed the singers to walk around the area and listeners. It was appropriate that we performed the work outside of the City Art Gallery, as it certainly felt as if we were all part of an art installation! Here is a short 3 minute video of the performance.

As John Luther Adams states, in the Inuit tradition, the spirit that animates all things is Sila, the breath of the world. As a result, one of the other major performance considerations of the work is that the musicians play their note or figuration to a duration lasting for a full exhalation. The length of this exhalation will be affected by a musician’s physique, the type of instrument being played, and the tessitura, among other considerations. But as the piece progresses one becomes acutely aware of the nature of breath.

Because of this focus on the natural physics of how sound is composed and the integral part that the sense of breath has on this work, the piece becomes a very meditative experience. As the composer states, “Music is a call to attention; an invitation to be more fully present in this miraculous world we inhabit”.

Certainly for those present throughout the performance, the meditative aspect of the work became very powerful indeed. At the conclusion of the work, as the work dissipates into the sound of breathing and then finally the ambient sounds of the environment, one could hear a pin drop! I think the listener can’t but help become intensely absorbed in the environment while experiencing the work and speaking personally, a profound sense of gratefulness can enter one’s consciousness as a result of its performance.

It was a privilege to present this work in Wellington and I applaud the New Zealand International Festival of the Arts for their decision to offer this profound musical experience free of charge to the people of Wellington. The two performances attracted 5000 people and without doubt added to the quality of life that New Zealand’s vibrant capital city offers its inhabitants.

For me, the run through New Zealand’s most famous track and the experience of the genius of John Luther Adams afforded me two complimentary meditative experiences that focused my mind on a sense of wonder and gratefulness for the environment that surrounds all of us.